Olympia’s Maid

Illustration by Jovilee Burton

Revisiting Lorraine O’Grady’s seminal essay on reclaiming Black female subjectivity 🌹

The Black female body has been a site of contention since as early as the 16th century. Often reduced to the sum of her parts, shrouded in harmful stereotypes of sexual deviance and primitiveness under the Western male gaze, the image of the Black woman remains tangled in what has been described as “a history of enslavement, colonial conquest, and ethnographic exhibition”. When re-examining representations of the Black female body throughout history, it is evident that Black women have often been portrayed as peripheral figures to the central subject of a work of art, and as a result, these harmful images have controlled and limited how Black women navigate society.

“the most vital inheritance of contemporary art is a system for uncovering the unexpected”

In 1994, American artist and writer Lorraine O’Grady penned Olympia’s Maid, an essay that theorised Black female subjectivity, focusing on the legacy of Édouard Manet’s painting Olympia (1863), and the significance of the artist’s depiction of Laure, the Black model who posed as a maid. In her essay, O’Grady examines representations of the Black female body in art, past and present, contemplating how Black women as subjects occupy art, from paintings to photography and beyond. From an art historical perspective, we tend to focus on the absence of Black women on gallery walls, but a factor just as important to consider, is their presence on those walls, and the subsequent problems that come with representation.

Olympia by Édouard Manet

With loose brushstrokes and a flattened composition, Manet’s Olympia is far cry from the carefully painted portraits of 19th century France. Olympia is depicted across a large canvas, reclining confidently on a chaise lounge. She poses nude for the painting with an almost confrontational gaze. Her posture suggests that she is comfortable with nudity, which is contrasted with the presence of fully-dressed maid, Laure. Manet adds small details to his nude muse, an orchid in her hair, a black ribbon around her neck, pearl earrings, a bare foot, all symbolising wealth and sensuality.

“Images of misrepresentation are even more consequential when it occurs within the realms of mass media and popular visual culture because the viewing audience is pervasive.”

In contrast, Laure appears hidden, blending seamlessly into the background of the painting; she gazes over at Olympia, offering her a bouquet. She is described by one art historian as “a deputy, or stand-in, a servant”, her presence is one of servitude and contributes to the discomfort felt by the viewer. Laure exists in the image as the antithesis of desire, “we know what she is meant for: she is Jezebel and Mammy, prostitute and female eunuch, the two-in-one” says O’Grady. The misrepresentation of the Black female body is evident in Olympia, as Laure is painted through the lens of Manet, resulting in an image that tells us very little beyond the stereotypes that we have seen continuously across art history and contemporary culture.

When Olympia was first exhibited in the Paris Salon of May 1865, the painting sparked outrage, with many describing it as vulgar and grotesque. Today, Olympia remains one of the most controversial works of the 19th century, notorious for its “feminist” imagery, and the idea that Olympia as a subject is challenging the infamous male gaze. Very few art historians offer any thoughts on Laure’s depiction, often completely overlooking her presence in the painting. The erasure of Laure from many discussions surrounding Olympia mirrors the ways in which BIPOC women are excluded from present day feminist movements and discourse.

Amongst Black art critics and curators, Olympia catalysed a different discussion, one around the presence of Laure. The painting inspired the 2018-2019 exhibition, Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today, at Columbia University’s Wallach Art Gallery, curated by Dr. Denise Murrell. “People have told me, ‘It’s not that I didn’t see the black maid in the painting, I just didn’t know what to say about her’,” Murrell shared with the Guardian.

UNTITLED (MAYA #4) by Mickalene Thomas

“The black female’s body needs less to be rescued from the masculine “gaze” than to be sprung from a historic script surrounding her with signification while at the same time, and not paradoxically, it erases her completely.”

Posing Modernity examined representations of the Black female body and the impact that the Black figure had on the development of modern art, featuring late 19th and early 20th century paintings by Édouard Manet, Frédéric Bazille, Henri Matisse, and many more. The exhibition also included works by Harlem Renaissance artists, Charles Alston and William H. Johnson, and contemporary artist Mickalene Thomas, highlighting the significant role that Black artists continue to play in reclaiming the Black body. During the 1920s and 1930s, Harlem Renaissance artists created more nuanced portrayals of Black figures, moving away from reductive stereotypes in which the Black body was often fetishised. In her essay, O’Grady encourages us to pivot our focus away from the masculine gaze and to examine what lies beneath the common tropes attached to Black womanhood. Murrell’s exhibition plays a major role in interrogating the Black female body as subject, and provides some much-needed context on the art that we see today.

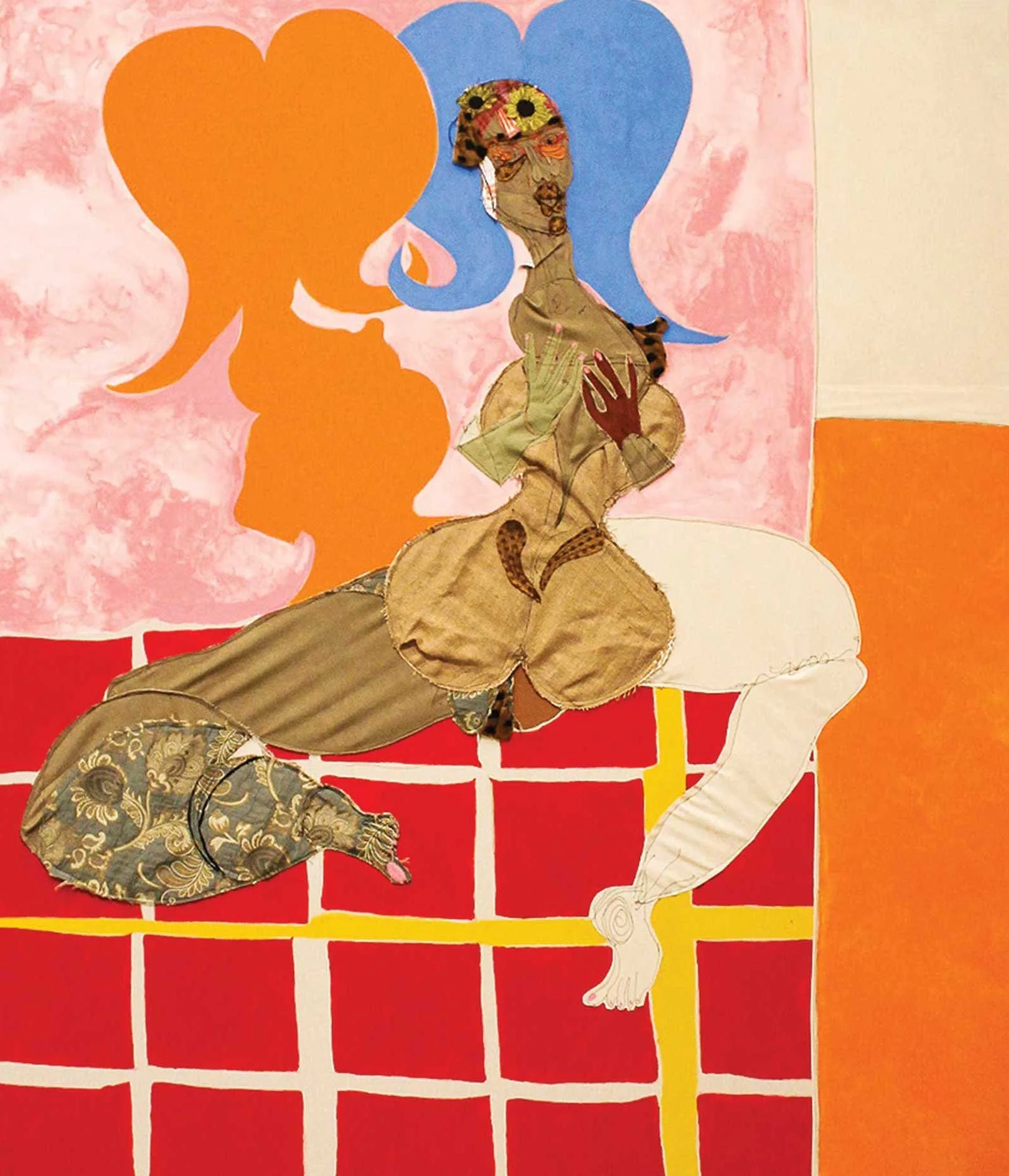

Yo Mama by Wangechi Mutu

In the same manner, many contemporary Black women artists continue to push boundaries, giving new meaning to Black female subjectivity. Kenyan-born American artist Wangechi Mutu explores sexuality and femininity in her work, depicting hybrid female forms in her collage paintings, sculptures, films, and installations. Her experimental practice examines self-image and the misrepresentation of Black women, centred around ideas of beauty and power. Similarly, Harlem-born artist Tschabalala Self explores the Black female body as subject, focusing on the implications of the Black female body within contemporary culture.

Loner by Tschabalala Self

In addition, Mickalene Thomas also touches on themes of beauty and power, creating layered collages that celebrate the Black female body. Thomas embraces eroticism as she reimagines the female form, her subjects exude sensuality as they appear adorned with glitter and rhinestones. “I love everything about the Black female body,” Thomas said in an interview with Vogue. Through introspection and self-discovery, Black women artists are acquiring the agency to change the narrative around Black femininity and attitudes that surround the Black female body. Many of today’s practising artists are engaging with new ideas and centring their own experiences. In contemporary art, we are witnessing the evolution of the Black figure, as it comes closer to subjectivity through the lens of Black women.

Though representations of the Black female body in art have changed within the past century, there is still a long way to go. When considering O’Grady’s thoughts on subjectivity, it becomes apparent that within contemporary art, Black female subjectivity is constantly evolving, both coming undone and being put back together in different ways. Black women are only just beginning to tell their stories, and continue to find new avenues for self-expression. Ultimately, reclaiming Black female subjectivity is not simply a destination, but more a frame of mind, a path to uncover the unexpected through art making.