False Spring

Kemi Onabulé in her studio

This month, we visited emerging artist Kemi Onabulé in her south-east London studio. Drawing inspiration from her Greek, English, and Nigerian heritage, Onabulé’s paintings explore the relationship between humans and the natural world, examining how our perception of nature has shifted over time. Scroll down for more 🍃

Photography by Dami Ayo-Vaughan

Addy: Kemi, so lovely to see you!

Kemi: You too, thanks for coming to the studio yesterday.

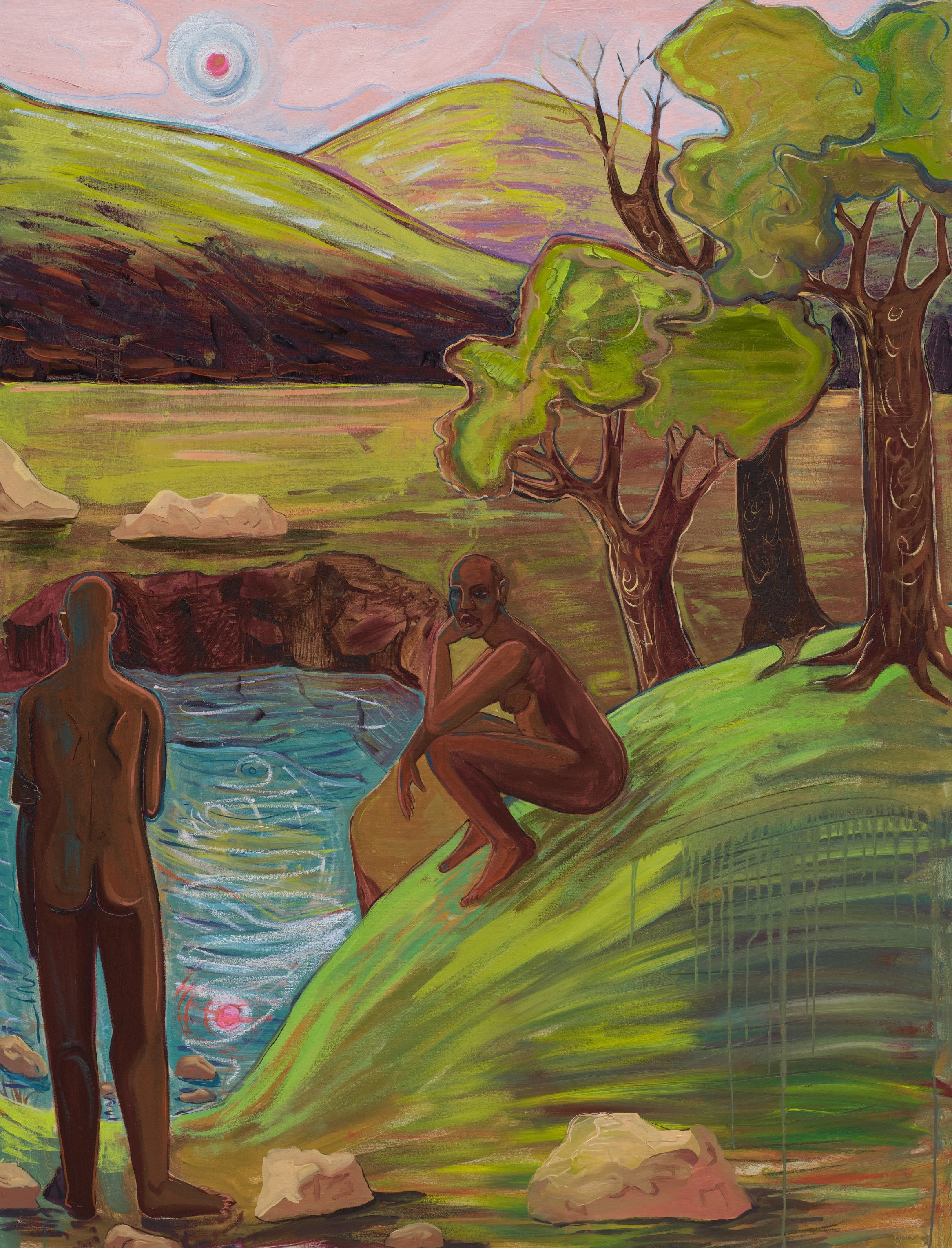

False Spring by Kemi Onabulé

Addy: Of course, we honestly had such a good time. What’s your earliest memory of art making?

Kemi: I don’t know how early I was interested in the visual kind of creating, that didn’t really capture my attention until maybe my teen years.

My earliest memory is probably playing in the garden, making up games. In my mind, that’s a form of art making or performance. I think it felt very purposeful. If one of the people involved got something wrong, I would correct them and be like, “No, this is the goal of the game,” almost like the methodology of the performance. It sounds funny, but I think kids can get into that level of intensity about play. So in that way, art making is similar. I equate that to the earliest form of creativity, or art making. Then obviously, scribbling in my parents’ books, but that didn’t seem as intentional.

Addy: I love that. I remember playing lots of different games as a kid, it was always so imaginative.

Kemi: Exactly. I remember the first time I was precious about something I’d made. I drew a giraffe, and my younger brother drew all over it. I think it’s the first time I realised that this was important, something I’d made. I didn’t want it to be destroyed, I wanted it to be preserved. That was quite an intense memory, poor guy.

Addy: Such a pivotal moment. You mentioned that it wasn’t until you were a teenager that you got more into visual art, like drawing, painting etc.

Kemi: That probably came about around 15, 16, not really until I was just about to start Sixth Form. Before that, I’d wanted to be a chef, an actor, anything really. I love football, I thought I’d do football for a bit, just anything that wasn’t sitting in a classroom, essentially. There was something about painting, I think it can be both very intellectual and mysterious. It brings together history, visual arts, and language. There’s something poetic about it. It just combined all of my interests.

The Wish To Be Forgiven by Kemi Onabulé

There’s also something quite performative about it. The act of painting has a long history. When you sit down in front of a canvas, you feel like you’re part of something. You’re part of a lineage that is very traceable and still very valuable and upheld. So I think I was quite aware of all of those things once I got into it. You go to a museum, and people treat that with a lot of reverence, similarly to going to a church. Energetically, I think I honed in on that understanding of what it meant to be a visual artist.

Addy: Yes, definitely. I love the comparison to the church, because both are such historic institutions. They have very different connotations, but are seen as cornerstones of Western culture.

Kemi: There are so many paintings in churches, they’re almost set up in the same way visually.

Addy: Lots of religious imagery in classical paintings. Your most recent solo show, “False Spring” at Night Gallery presented figures within post-apocalyptic landscapes. What inspired this body of work?

Kemi: I think my paintings have definitely gotten darker, not just colour wise, but also subject wise. The figures have become much more downcast and lonely and still. Walking around the city, five or six years ago, London felt like the best place in the world. It had so much energy. Maybe that’s the naivety of being younger, but I think a lot of spaces have become much more corporate, more cold, and designed for a certain kind of person.

Show Me Your Future, I’ll Show You My Past by Kemi Onabulé

In terms of the environment, the natural world is being destroyed at an enormous rate. There are things I remember from being a child, sounds from nature that I don’t hear anymore, like certain types of birds or frogs. I feel like in the summer, all you’d hear were frogs making noises. I don’t think I’ve heard that in about 10 years. All of this missing landscape, missing engagement, interaction, is kind of filtering through into my paintings. I don’t believe it’s necessarily symptomatic of my life, I think it’s a universal experience that people are going through, at least in the West.

Addy: Definitely.

Kemi: Yeah, very cheerful.

Addy: Do you feel like that was the starting point for you, and then it kind of evolved from there?

Kemi: For me, the ideas come very organically. I was reading a book by Hemingway about the turn of the century, just after the First World War. He wrote about Paris’s golden age. Europe had been through so much—physical, social, ecological destruction, poverty, hardship. Yet, what followed was a catharsis. I think we’re in a similar situation now, but haven’t reached that catharsis yet.

Things are shifting in ways they haven’t for a century. I’ve been wondering what this specific moment means and how people feel. Having a family who’ve emigrated for different reasons makes me more sensitive to these moments as well.

Addy: We’re witnessing lots of change at the moment. How did this exhibition differ from your previous work, if at all?

Kemi: I think it was much more linear, more tied to the subject and attitude that I’ve been trying to convey. In some ways, the show was a repetition of a very specific motif of a lone figure in a landscape. There’s a level of generalisation about the figure. In one piece there are two figures present, which is much more verdant. Generally, it’s less important for me to provide a story or a place that these figures occupy. It’s more about the feeling that the paintings exude. Together, they’re quite cohesive, I would say. In fact, we removed some of the slightly more cheerful paintings, so that we could maintain that level of mystery in the show.

Addy: You can really sense a shift in mood/tone in these newer works. Can you describe your creative process?

Limbes by Kemi Onabulé

Kemi: I showed you some of the watercolours in the studio, that’s always been something that I’ve played with a lot. I used to work with coloured pencil, when I had a bit more time and my children didn’t want to take them away and use them themselves. (Laughs)

I’ve always done detailed preparatory drawings. But then once I start painting, I might not look at it for a week or two, let it drift from my mind, and then come back to it in a more fuzzy way. It might sound odd, but I think with painting, at least the way I paint, when it’s rooted in imagination, you shouldn’t be too direct. You need to give it space, let it percolate. Sometimes, I’ll draw from the painting I’m working on, kind of loosen my hand up through drawing whilst I’m painting. It’s not about accuracy, just about experimenting with line or the overall mood of the painting.

Addy: I love that. In one of the works that we saw in the studio, you were drawing over the paint, which was really cool.

Kemi: Yeah, there’s also drawing within the paintings. I don’t feel the need to model paint, to create a lot of light and shade, that usually happens through line or through depths, rather than dynamics within the painting.

Addy: Would you consider yourself a slow painter? Do you prefer to spend time with your work, or does it depend on the vision for the piece?

Kemi: Every painting is different. Some paintings, I start them, do them really quickly, and I know that they will never see the light of day. It’s like the minute I start painting, it could be that the proportion is off, or the colour, but I feel the need to keep going, just to learn something from it.

Other paintings, I might do one very loose layer, leave it for two weeks, come back, do more, and not much is changing each time. Like the large painting you saw with the figure swimming, that’s been going on now for maybe two months. There was originally another painting underneath it. It was one of those paintings that, when I started, I thought, this is just shit. (Laughs) So I turned it horizontal and painted over it. Out of that came something different. The painting on top has no relationship to the painting underneath. But, in some way, they inform one another.

Addy: Yes, I love that you didn’t just throw it away or grab a new canvas and start over.

Kemi: I’m not that rich. Gotta use that canvas. (Laughs)

Addy: Always! It’s amazing that you transformed it into something entirely new.

Kemi: The paintings that I paint over have a specific character and style within my oeuvre. It’s very interesting how they’re often thicker and a lot more expressive, maybe to get rid of the marks underneath. The new painting is, in some way, being employed for the next painting, actually.

Addy: It’s like building layers and depth, it feels richer in a way.

Kemi: Yes, I think so.

Addy: What do you find most rewarding about the process of translating your ideas from drawing to painting?

Kemi: I think I get the most satisfaction out of the process. With printmaking, you put an intentional mark down then you reveal it, and it could result in something completely different. The way that you apply the ink on the plate could change the final image. In that way, it’s very satisfying, because your ego is not in it. You could do something and it could change, and it doesn’t really mean anything.

Painting, I still struggle to feel satisfied with. It takes me months to fully engage and enjoy it. I like to take the pressure off, so the painting with the panels you saw gave me a lot of satisfaction. The longer I’ve looked at it, the more I appreciate what I did. It’s a good piece, and I’ll try that approach again. There’s a lot of drawing involved in it.

Addy: That makes total sense. Do you feel like your relationship with certain works has ever changed based on external responses?

Kemi: In a way, I’ve been lucky over the last few years to have a necessary tunnel vision, maybe as a result of having children or perhaps the pandemic. When you’re young, you absorb the things that people tell you, and naturally that has reduced for me, the more involved I am in my own practice.

If I really appreciate something in a painting, I will explore it. But when other people like things, or say “I don’t like that, I like that,” I’m less bothered by it. I’ll pick up on it, as it’s nice to feel rewarded for things that you’ve done, but I think maybe I care less now, I’m more invested in what I’m trying to achieve with the painting.

Addy: That’s a great answer. It shows a level of maturity in terms of not being as fixated on other people’s opinions and just being very in touch with your own practice. That’s so important, especially as an emerging artist, because there’s always so much noise around you, and that can come with its own challenges. It’s good that you trust yourself and your vision.

Kemi: I try.

Addy: What personal experiences have shaped your fascination with nature and its role in human life?

Kemi: Growing up with a mother who grew up in the countryside, in Somerset, really influenced me. She had a particular attentiveness towards nature, and we’d often go blackberry or apple picking. She was very invested in us spending time outdoors, and we were home educated until the age of 11.

Addy: Oh wow, I didn’t know that.

Kemi: Yeah, we had a lot of time to explore our natural instincts and learn in our own way. I developed a tactile way of learning and loved being outdoors, which I was able to use to my advantage. I think that gave me a sensitivity towards landscapes from a young age. My sister hates being outside, but no one forced her to stay there. She was happy to read inside.

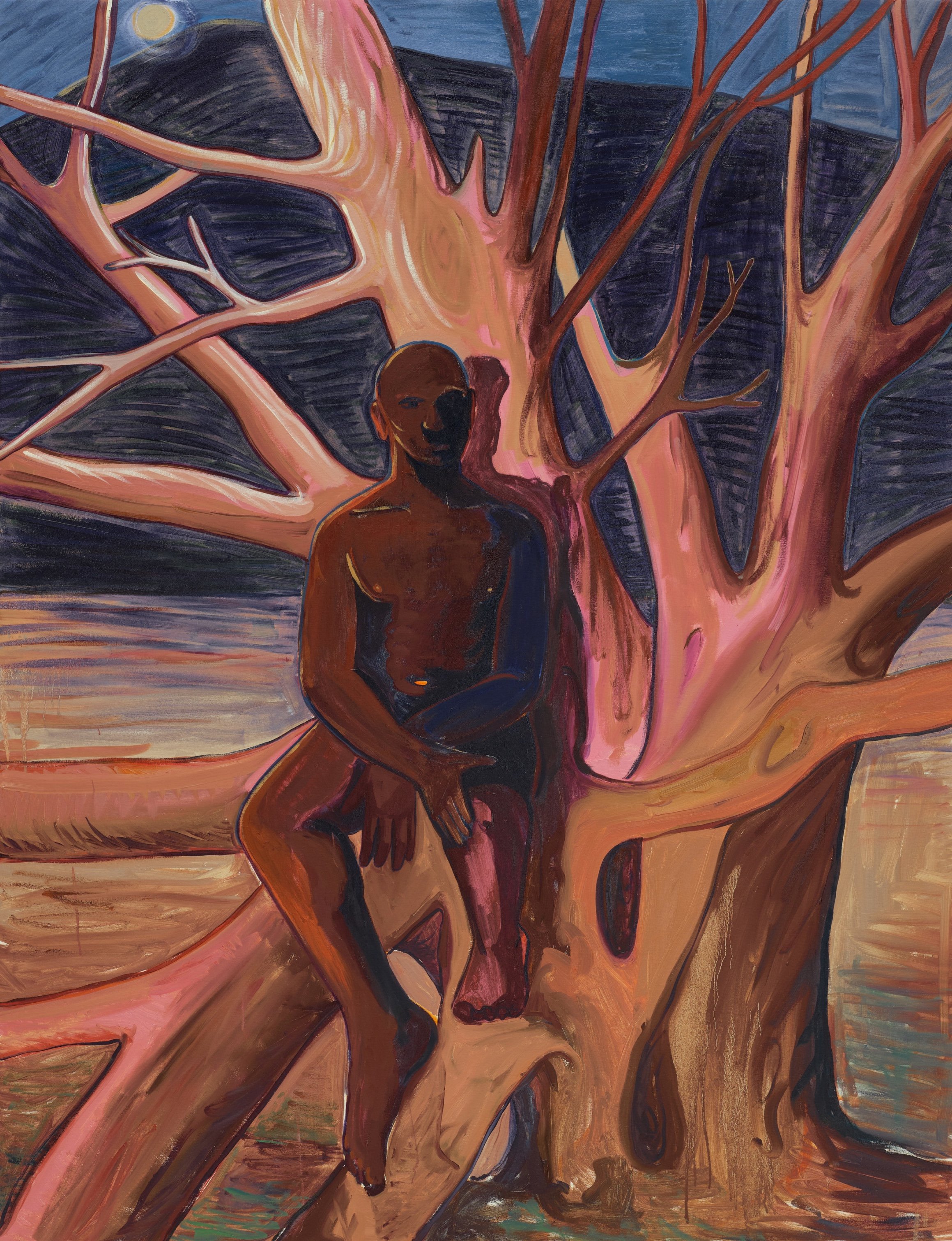

Blood Moon by Kemi Onabulé

We were able to pick up on what we liked and what we engaged with the most, and were given the free space to do that independently. I also went to school out in the countryside for a period, so that further cemented my exposure to nature. It was a very lucky childhood.

Addy: I feel like we’re part of that cusp where we grew up playing outside, but then our early adolescence was also very digital. What do you find the most challenging about being an artist?

Kemi: The mental fortitude, the need to keep believing. I’m not a religious person by nature, I’m quite devoid of belief, but there’s a need to believe that things will continue to grow and I’ll be able to keep making art. I’m a very reward driven person. So, I love having shows, I like people to see the work. I want people to talk about it, not because I need attention, but because I really believe in the conversations that the works bring up, especially for Black and Brown people.

For people to see somewhat similar versions of themselves in a landscape and imagine beyond their own situations, because we all know what it’s like to be in our bodies. It can feel very much like a cage sometimes. So for me, it’s worth going through the challenges of being an artist because of all of these reasons.

The challenges are job security, money consistency, access to spaces that will allow you to grow your practice. London is essentially one of the only places in Britain where you can have a practice and if you work in a certain way, it will possibly reach the world. But with that comes a certain level of need for money, and privilege, and access, and it’s getting harder for people. I think all of that definitely influences my perspective.

Addy: Totally, there are lots of conversations happening at the moment around accessibility, which is so important. Do you have a favourite piece of work that you’ve created?

Kemi: There’s one called A Place To Hide (2020). It’s a figure in the middle of a landscape and the eyes are really wide. It’s influenced by specific artists like Belkis Ayón, so there’s a very strong lineage in that painting. I think it’s the first time I started really thinking about this generalised figure and the landscape, and developing my own world-building, moving away from just a figure in a landscape.

A Place To Hide by Kemi Onabulé

I want to do that more, where I merge the figure, and use the textures of the landscape as the skin. So yeah, I think that’s my favourite work.

Addy: Amazing, I like the idea of merging the figure with the landscape. It feels very surreal, especially in terms of what that merging signifies. There’s a lot to unpack.

Kemi: Yes, it’s very tied to the idea of cloaking or disguising yourself. I’m very interested in that concept, taking away people’s assumptions of something or somebody.

Addy: It becomes even more layered when it’s Brown and Black bodies being depicted.

Kemi: Exactly.

Addy: Last question! How has your practice evolved over time?

Kemi: It’s grown in terms of scale, because I’ve been lucky enough to change studios and have access to better materials and an assistant who can help stretch canvases. Now that I’m not always doing the physical labour, I feel more free to just paint. The limitations of constantly worrying about, using paper of a certain scale and thinking “Can I pay for it? Or should I eat?”, has slightly receded. When that happens with artists, we always choose the paper.

Instructed to Look by Kemi Onabulé

Also, the subject matter has become wider ranging, a bit closer to home, and more about my concerns, my anxieties, and less about imagining a better world, so to speak. Instead reflecting maybe a parallel version of what I feel is happening in the world. It feels more personal.

Addy: Yes. Even stylistically, we were saying yesterday, you’ve sort of kept the same motifs but you’re applying them in a more experimental way, which is so exciting to see.

Kemi: Thank you. Yeah, I hate staying the same.

Addy: I’ve noticed! Okay so, at the end of interviews, I like to do something called a rapid fire round 🔥🔥 it’s basically just like quick fire questions. Renaissance or Baroque?

Kemi: Renaissance.

Addy: Oil or watercolour?

Kemi: Ooh… Oil.

Addy: I wasn’t sure what you were going to pick, actually.

Kemi: I do love watercolour.

Addy: Books or films?

Kemi: Books.

Addy: Nice. Tea or coffee?

Kemi: Coffee. I drink a lot of coffee, it’s like an issue.

Addy: Dogs or cats?

Kemi: Dogs. I do not like cats.

Addy: Cats scare me lowkey.

Kemi: Not so fun.

Addy: Summer or winter?

Kemi: Summer.

Addy: Sweet or savoury?

Kemi: Sweet.

Addy: Early bird or night owl?

Kemi: Early bird.

Addy: You’re a mum, so I imagine you have to be up quite early!

Kemi: Even before, I’d always be up at seven, it’s like chronic. I wish I’d taken more time to sleep. (Laughs)

Addy: Biggest fear?

Kemi: That the world is getting more unstable.

Addy: That’s a very valid fear.

Kemi: I think that’s my general fear, yeah.

Addy: I was thinking more like, you know, spiders.

Kemi: None of that bothers me. It’s very, very existential.

Addy: So real. Finally, the last song that you listened to?

Kemi: Lonely Fight by Mk.Gee.

Addy: I’ll add that to my list. Kemi, thanks so much for taking the time to answer all of my questions and for inviting us to your studio! It was great.

Kemi: It was so nice. The questions were great as well.

Addy: Thank you <3 have a lovely week and see you soon!

For more from the wonderful Kemi, check out her website here!